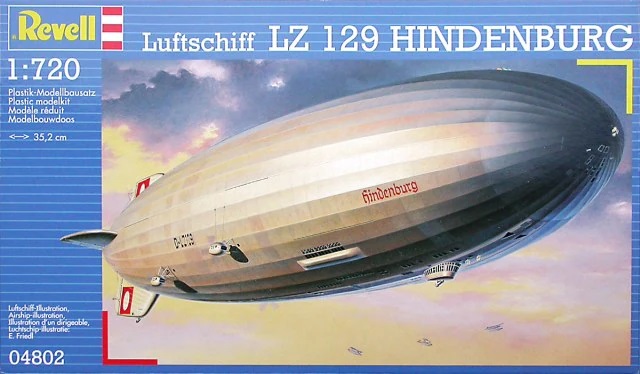

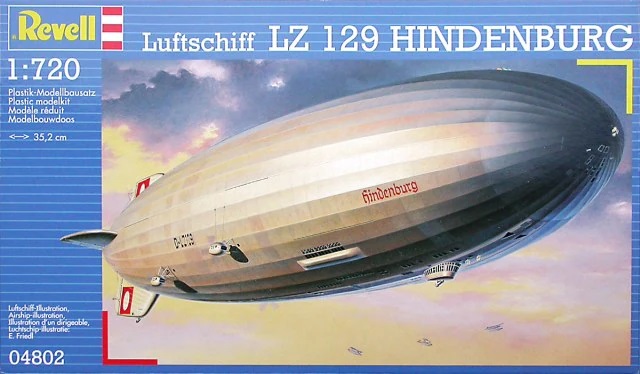

Revell LZ129 1:720 boxtop

by Ley Reynolds

Historical Notes

Reports and theories about lighter-than-air flying have be around since at least the early 1400's, but it was first demonstrated in 1783 by the Montgolfier brothers in France with a hotair balloon. Soon thereafter hydrogen (discovered in Britain in 1766) replaced hotair, initially again in France. Eventually the military saw the advantage of captive balloons for reconnaissance and artillery spotting, these being employed in the US Civil War, Franco-Prussian War, the Boer War and the Great War. Barrage balloons were also used extensively during World War 2 and non-rigid or pressure-airships were deployed for anti-submarine surveillance by the Royal Navy during the Great War and by the US Navy in World War 2 (blimps).

However there were many drawbacks with both these types which were largely overcome by rigid airships, which had a framework of aluminium or timber enclosing hydrogen filled gas cells. This idea is often described as the brainchild of Count Ferdinand Adolf August Heinrich von Zeppelin, although, in truth, many engineers were working on the concept in the 1890's in Germany, Austria, Britain and France virtually simultaneously. Nevertheless Zeppelin, a wealthy General in the Deutsches Heer with contacts throughout the ruling class rather than an engineer, did much to promote rigid airships in Europe in the early-1900's. His first four craft, LZ1 to 4, could probably be termed "proof-of-concept" airships, but following the crash of LZ4 his company was practically bankrupt. Public donations after this catastrophe allowed the Count to form Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmbH, employ talented engineering staff and embark on the design/production of evermore practical craft at Friedrichshafen using aluminium alloy framework.

At about the same time Professor Johann Schutte, an engineer who taught at the Danzig Technical High School's Department of Shipbuilding, set up Luftschiffbau Schutte-Lanz at Mannheim and similarly embarked on the design/production of rigid airships but with timber framework. Some of his work such as the hull shape and the design of the tailplanes was far in advance of Zeppelin's and eventually, under pressure from the military, Schutte was forced to share his patents with the former.

The outbreak of the Great War saw both the Deutsches Heer and Kaiserliche Marine adopt rigid airships - the former for tactical bombing and the latter for maritime reconnaissance and strategic bombing, the last because of their great endurance and range. Within twelve months the DH realised that tactical operations on the Western Front only led to prohibitive losses, although such sorties could still be carried out on the Eastern Front. By 1916 they saw airships as an aeronautical dead-end and abandoned their use entirely in favour of mutli-engined aircraft.

In an early example of Teutonic stupidity, the KL, perhaps because they were generally unable to successfully attack the much larger Royal Navy, their main opponent, and based on an astonishing degree of wishful thinking, chose to ignore the airships' limitations. This led to the construction of a large number of ever larger Zeppelins (the KL was a very reluctant user of the Schutte-Lanz craft), all requiring more extensive infrastructure and thousands of troops for ground handling. These were then employed for strategic bombing over Britain, mainly on London and the industrial Midlands. Such attacks were undoubtedly terrifying for the general population but the amount of actual damage was minimal. The main problem for the KL was the primitive means of aerial navigation available at that time. This meant that the crews had no real idea of the ship's location and Zeppelins basically wandered aimlessly over the countryside scattering bombs wherever lights showed on the ground (on occasion killing more livestock than people). As the British aerial defences improved the result was more and more Zeppelins destroyed.

By mid-1917 the Schutte-Lanz ships had been wfu (withdrawn from use) and all were broken up by year's end. Zeppelin production continued, albeit in small numbers, while losses still occurred regularly - the last being L.53 near the Dogger Bank South Lightship on the 11th of August 1918. With the defeat of the Central Powers, a small number of airships were delivered as part reparations and the rest destroyed either by their crews or by the Allied Control Commission.

Development of rigid airships was ongoing during the 1920's in Britain (notably by Barnes Wallis), France, Germany and the United States, but by 1933, following even more losses, and this in peacetime, and the continued development of long-range aircraft, only the most diehard proponents refused to accept that the airship was passed its "sell by date". Perhaps unsurprisingly these proponents were German and almost all employed by Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmbH, with the company now largely financed by the Nazi Government. Ironically, or perhaps fittingly, many were killed in the destruction of the Hindenburg on 6th of May 1937, leaving just the Graf Zeppelin II under construction. In 1939 this ship only flew about thirty operations, one third being ELINT flights off the East coast of Britain probing early radar signals. Whatever, if anything, these flights discovered seems to have been ignored by the Luftwaffe.

Airship Types

There was a plethora of different Types during the Great War (Types "a" to "x" from Zeppelin and Types "a" to "f" from Schutte-Lanz) so only the more significant will be covered below.:

Type Length----Hull Dia.----Built----Maybach

Engines

Schutte-Lanz;

"e", SL.8 Class 174.0m 20.1m 12 4 x 240hp

"f", SL.20 Class 198.3m 23.0m 3 5 x 240hp

Zeppelin;

"m", L.3 Class 158.0m 14.9m 12 3 x 180hp

"p", L.10 Class 163.5m 18.7m 22 4 x 210hp

"q", L.20 Class 178.5m 18.7m 12 4 x 240hp

"r", L.30 Class 198.0m 23.9m 17 6 x 240hp

"v", L.53 Class * 196.6m 23.0m 10 5 x 245hp**

* - colloquially known as the Height Climbers having a lightened structure and a maximum operating altitude of 6500m.

** - the rear two engines geared to one propeller.

As shown above, the main identifying features were length, hull diameter and number of engines/propellers, while the hull shape was basically unchanged. Zeppelin: Rigid Airships 1893 – 1940 by Peter Brooks, Putnam 1992 includes small scale drawings of all Types, while Zeppelins: German Airships 1900 – 1940 and Zeppelin vs British Home Defence 1915 – 1918 from Osprey Publishing are useful. There are also some relevant titles in the Windsock series of monographs. Finally cyberspace has numerous articles, although the accuracy of many (most?) of these is often doubtful.

The Kits

Kits are available in 1/720th scale from Revell and Mark I and in 1/350th scale from Takom, both as shown hereafter.

1003828-12741-42-pristine.jpg |

1004120-12741-23-pristine.jpg |

1004121-12741-27-pristine.jpg |

1074158-31722-83-pristine.jpg |

1359457-27571-26-720.jpg |

1359460-27571-43-720.jpg |

155011-16236-65-pristine.jpg |

Reviews

Mark I - 1/720th Scale Zeppelin P Class Airship - This is an injection moulded kit containing 38 parts including a three-part cradle stand. All parts are neatly moulded with no flash but many are minute and will require VERY careful removal from the sprues and gluing in place. In fact these seem to be the major problem in assembling the kit but presumably anyone with experience of 1/700th scale ships would have little trouble. Decals are provided for markings, bomb-bay doors and gondola windows. The Q Class kit includes two extension pieces for the longer hull.

Takom - 1/350th Scale Zeppelin P Class Airship - Again an injection moulded kit, this time containing 46 parts plus a small etch-brass fret. A clear three-part stand is also included. There is no flash and at this larger scale surface detail is better and assembly much easier. A small decal sheet provides markings and the Q Class has two extension pieces for the longer hull.

Other Airship Types/Classes

Conversion of any of the above to another Type/Class is reasonably simple, involving shortening or lengthening the hull and possibly increasing its diameter. In either scale the differences in the gondolas is so small as to be insignificant although some changes may be necessary to the outriggers/propellers.

Ley Reynolds

Use the index button to return to the main issue 36/4 index.